Curr

Curr

H&E naturist publisher Sam Hawcroft was tasked with collecting Murray Wren’s large photo library – and, as she did so, she began piecing together the life of this fascinating New Zealand-born eccentric…

For a man who edited the world’s oldest and most famous naturist magazine in its heyday, surprisingly little is known about Murray Wren. Just after Christmas 2013, Wren died, aged 94, alone in his poky flat in Blackheath Park, south-east London, leaving behind him piles of archive material covering decades of naturism in Britain and all over the world. It transpired that Wren had bequeathed his collection to H&E.

I first met Murray Wren – who edited H&E for much of the 1970s and contributed articles and photographs for many years before he took over – about five years ago, when I went down to his flat and chatted with him for a few hours. Hearing he had died was not too much of a shock for me; after all, he had reached a grand old age and had been growing increasingly infirm. But I was nevertheless saddened by the news, as I had been hoping to get back in touch with him and see him again before the inevitable happened… as ever, life and work got in the way, and, to my sincere regret, I never got around to making contact again.

I first met Murray Wren – who edited H&E for much of the 1970s and contributed articles and photographs for many years before he took over – about five years ago, when I went down to his flat and chatted with him for a few hours. Hearing he had died was not too much of a shock for me; after all, he had reached a grand old age and had been growing increasingly infirm. But I was nevertheless saddened by the news, as I had been hoping to get back in touch with him and see him again before the inevitable happened… as ever, life and work got in the way, and, to my sincere regret, I never got around to making contact again.

It was rather strange turning up at Hallgate, the small apartment block in the highly desirable gated community of Blackheath Park, five years on, and this time in a small hire van. The flat was largely bare, and the threadbare, stained, dark-green carpets and ancient decor were evidence that an elderly, eccentric man had lived there for many years without ever having any modernisation work carried out. Among one of the many photographs I discovered was one of his third wife, Helene, standing in the kitchen of the flat, in what must have been no later than the mid-1970s.

Archives

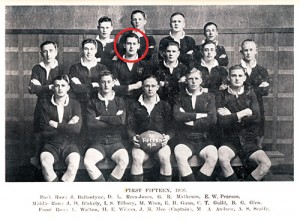

Among the thousands of pictures of pretty girls in various states of nudity from naturist to mild erotica (I think it’s safe to say Wren was a bit of a ladies’ man), there was the odd gem, such as a battered 114-year-old copy of a bizarre tome called Anomalies and Curiosities of Medicine, a 1936 Waitaki Boys’ School yearbook including a photo of a teenage Wren in the rugby first team, and a set of architecture diploma certificates he achieved at the University of Auckland. I say “gems” – these things are quite obviously worthless in monetary terms, but for me, they offer fascinating glimpses into the life of this strange old man, who was born in Dunedin, New Zealand, in around 1920.

Among the thousands of pictures of pretty girls in various states of nudity from naturist to mild erotica (I think it’s safe to say Wren was a bit of a ladies’ man), there was the odd gem, such as a battered 114-year-old copy of a bizarre tome called Anomalies and Curiosities of Medicine, a 1936 Waitaki Boys’ School yearbook including a photo of a teenage Wren in the rugby first team, and a set of architecture diploma certificates he achieved at the University of Auckland. I say “gems” – these things are quite obviously worthless in monetary terms, but for me, they offer fascinating glimpses into the life of this strange old man, who was born in Dunedin, New Zealand, in around 1920.

Wren fancied himself as something of an artist, too – among the piles of stuff left in his flat were sketchbooks and pads. There was a set of images of Wren himself, presumably taken on his camera’s self-timer in the 1950s or 1960s, showing that he was a fine figure of a man back in the day.

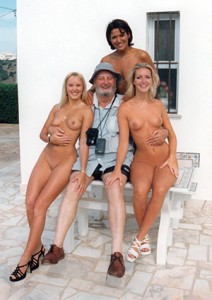

Even when he was well into his 70s and 80s, Wren still travelled to naturist resorts around the world to go on photoshoots. There were scores of packets of 35mm film images developed by Doubleprint and Truprint (remember them?) from the 1990s and early 2000s. While Wren’s collection was quite haphazard when I came to it, I’m sure it had originally been very well organised, as everything was meticulously labelled in his own handwriting, and most images had stickers with “Murray Wren Picture Library” printed on them. By the time I met him a few years ago, his sight had begun to fail and he wasn’t great on his feet, but he didn’t strike me then as particularly reclusive. Eccentric, yes, but not reclusive, as he surely wouldn’t have entertained meeting and chatting to me otherwise. He could, after a fashion, use a computer, as he did from time to time send me emails and CDs. He was very sharp-witted, with a keen sense of humour.

Even when he was well into his 70s and 80s, Wren still travelled to naturist resorts around the world to go on photoshoots. There were scores of packets of 35mm film images developed by Doubleprint and Truprint (remember them?) from the 1990s and early 2000s. While Wren’s collection was quite haphazard when I came to it, I’m sure it had originally been very well organised, as everything was meticulously labelled in his own handwriting, and most images had stickers with “Murray Wren Picture Library” printed on them. By the time I met him a few years ago, his sight had begun to fail and he wasn’t great on his feet, but he didn’t strike me then as particularly reclusive. Eccentric, yes, but not reclusive, as he surely wouldn’t have entertained meeting and chatting to me otherwise. He could, after a fashion, use a computer, as he did from time to time send me emails and CDs. He was very sharp-witted, with a keen sense of humour.

Obscurity

All of which makes it harder to understand why he died in such obscurity; there were only seven people at his funeral. He’d had, by all accounts, three wives, but was never interested in having children. A bit of research tells me that Helene Wren, who was about seven years older than Murray, remained with him until she died in 1996, in her early 80s.

Wren continued to go on naturist photography shoots after Helene’s death, and as late as 2007, he wrote a piece for H&E on the magazine’s history, to mark the 10th anniversary of its takeover by New Freedom Publications. However, as he approached his 90s and his health began to fail, he became virtually housebound.

Wren continued to go on naturist photography shoots after Helene’s death, and as late as 2007, he wrote a piece for H&E on the magazine’s history, to mark the 10th anniversary of its takeover by New Freedom Publications. However, as he approached his 90s and his health began to fail, he became virtually housebound.

I do find it odd that, while he must have made hundreds of acquaintances in his years of being an architect, travelling around the world, and editing H&E, he stayed in contact with very few people. He had easily enough money to either have his flat modernised or move somewhere where he could get the very best of care – but, for whatever reason, he just didn’t.

If one searches the internet for Murray Wren, very little indeed turns up, which is a great shame when one considers the pivotal role he played in one of the world’s most historic magazines.

I’m not sure whether I feel I ‘know’ Wren any better now, having had this chance to glimpse into his past, though I think it rather confirms my belief that he was highly intelligent, attractive, charismatic and creative – yet deeply complex. He perhaps never quite got over the death of Helene, and, despite his wealth, was unable to come to terms with his increasing frailty.

Hopefully the images on this website prove to be a fitting tribute to a man who did much to capture the joys of naturism and of being naked.

- A version of this article first appeared in the June 2014 edition of H&E naturist magazine.